Startups race to make steel cheaply and cleanly

Latest News

Boulder, Colo.— Clean steel of the future may be brought to us by a sparkling white office building nestled here in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

This building, headquarters of startup Electra, houses a large chemistry lab full of dozens of engineers and scientists buzzing about in blue lab coats and safety goggles.

It’s a far cry from the gigantic greying steel tanks and emissions-belching smokestacks we associate with the iron and steel industry, where workers don hard hats to shovel coal into red hot furnaces.

“Our vision is to bend the trajectory of climate change by decarbonizing ironmaking, a key first step in making steel,” Electra CEO and co-founder Sandeep Nijhawan, told Cipher. “At Electra, we don’t just want to reduce CO2 emissions, we also want to extract value from waste and revolutionize steel production, consumption and recycling.”

Steel is crucial to modern life, used to make everything from wind turbines to sewing needles. But making it accounts for at least 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions due to that red-hot furnace process.

Now a handful of companies in Europe and the United States are racing to create cost-competitive iron that will be made into steel with low or even no emissions. Electra and at least one other U.S.-based startup, Boston Metal, aim to combine cheap renewable energy with new production processes to take on traditional steel.

The companies will compete against fossil-fuel steelmakers who have a massive cost advantage, but also against other startups trying to make clean steel other ways, especially with hydrogen or carbon capture technologies.

Put simply, it’s a race to lower costs on two fronts: With incumbents and with each other.

Most of today’s steel is made via a couple of different methods that require fossil fuels and extremely hot temperatures (more than 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit).

In contrast, Electra and Boston Metal use electricity to chemically separate iron — the most energy-intensive part of the steelmaking process — without releasing any carbon dioxide emissions.

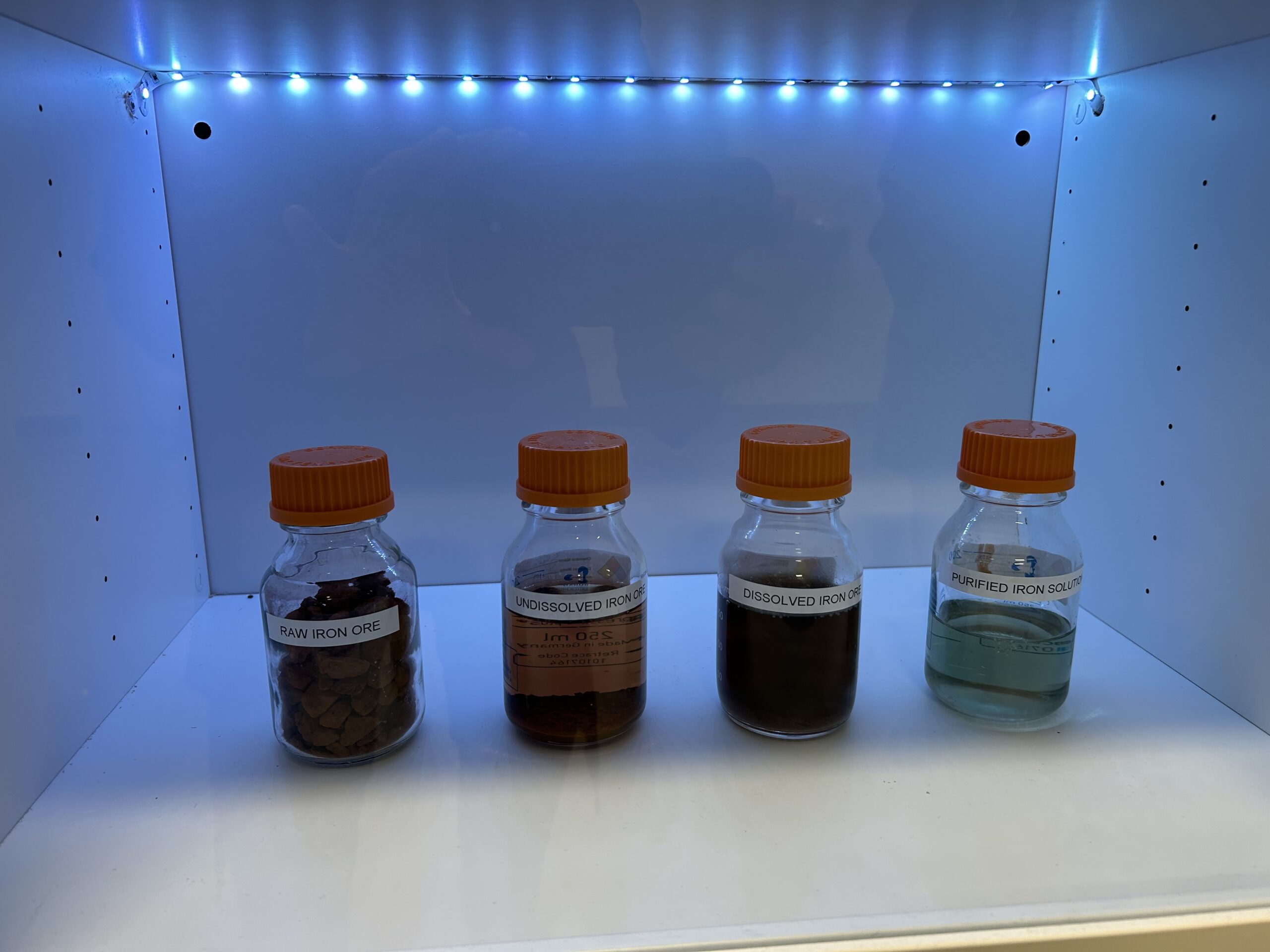

Chemistry at work: Electra turns raw iron ore into an iron plate by dissolving it in acid and running electricity through it. Credit: Amena H. Saiyid.

Electra says it will be able to lower costs by purifying iron from low quality iron ores often lying as waste at mines and by harnessing variable renewable energy when it is least expensive, said Nijhawan.

The company’s proprietary process doesn’t require high heat, meaning it can occur at the same temperature as a cup of coffee sitting on a table, and can be stopped and started to match renewable energy from wind, solar or hydro, he told Cipher while on a tour of their headquarters.

What’s more, Nijhawan said, the process avoids the cost of buying and storing renewable-sourced hydrogen or installing carbon capture tech if using natural gas.

As the world transitions away from fossil fuels, corporations are seeking clean, cheap steel to reduce supply chain emissions from their end products, which range from vehicles to solar panels to buildings, said Chathurika Gamage, principal with RMI’s climate-aligned industries.

New laws in the U.S. and Europe are also nudging the economics toward clean steel’s favor — along with the bet on cheap and plentiful renewable energy.

With the European Union launching the world’s first border carbon tax this October on certain high emitting imports, including iron and steel, manufacturers in the U.S. will need to act fast to keep up with European steelmakers who have more low-carbon steel projects in the pipeline.

Despite these growing pressures, no commercially available clean steel plants are in operation yet in the world, Gamage said. The pipeline of projects, basically all of which are outside of the U.S., suggests hydrogen-powered steel is the favored approach.

Globally, 78 projects are aiming to make low-carbon steel from clean hydrogen, with most of the commercial-scale ones planned for Europe, according to a World Economic Forum-supported global green tracker.

A project in France from steel manufacturing giant ArcelorMittal is the only other pilot attempting to use electricity to extract iron from ore, like Electra and Boston Metal.

Clean steel can also be made with natural gas and carbon capture and storage (CCS). But CCS technology has to date only been used successfully and commercially at the Emirates Steel plant in Abu Dhabi. Natural gas is cheap and abundant there, and ample room nearby allows for storage, said Hasan Muslemani, a senior research fellow who heads carbon management research at the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies (OIES).

Think tanks RMI, OIES and Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy say using hydrogen made from renewable electricity may prove to be the most economical approach to making low-carbon steel globally because the technology is available today at commercial scale.

Sweden’s Hybrit project exemplifies this best. Located in the “haven of cheap and green energy,” Hybrit is taking advantage of the country’s ample supplies of clean, cheap and steady fossil-free power to make steel with renewable hydrogen, said Muslemani.

Companies in the U.S. may follow suit as generous federal subsidies from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act start going to both renewable electricity and hydrogen directly.

Switching to an electricity intensive approach favored by companies like Electra, Boston Metal and ArcelorMittal could be economical depending on “where you are, where your electricity comes from and what it costs,” said Zhiyuan Fan, senior research associate at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

Where natural gas is abundant and cheaper than renewables, then this approach would likely be more expensive, Fan said.

Electra Chief Technology Officer Quoc Pham said his firm is actually saving money by not running their operations around the clock, unlike traditional steelmakers and even other newcomers like Boston Metal.

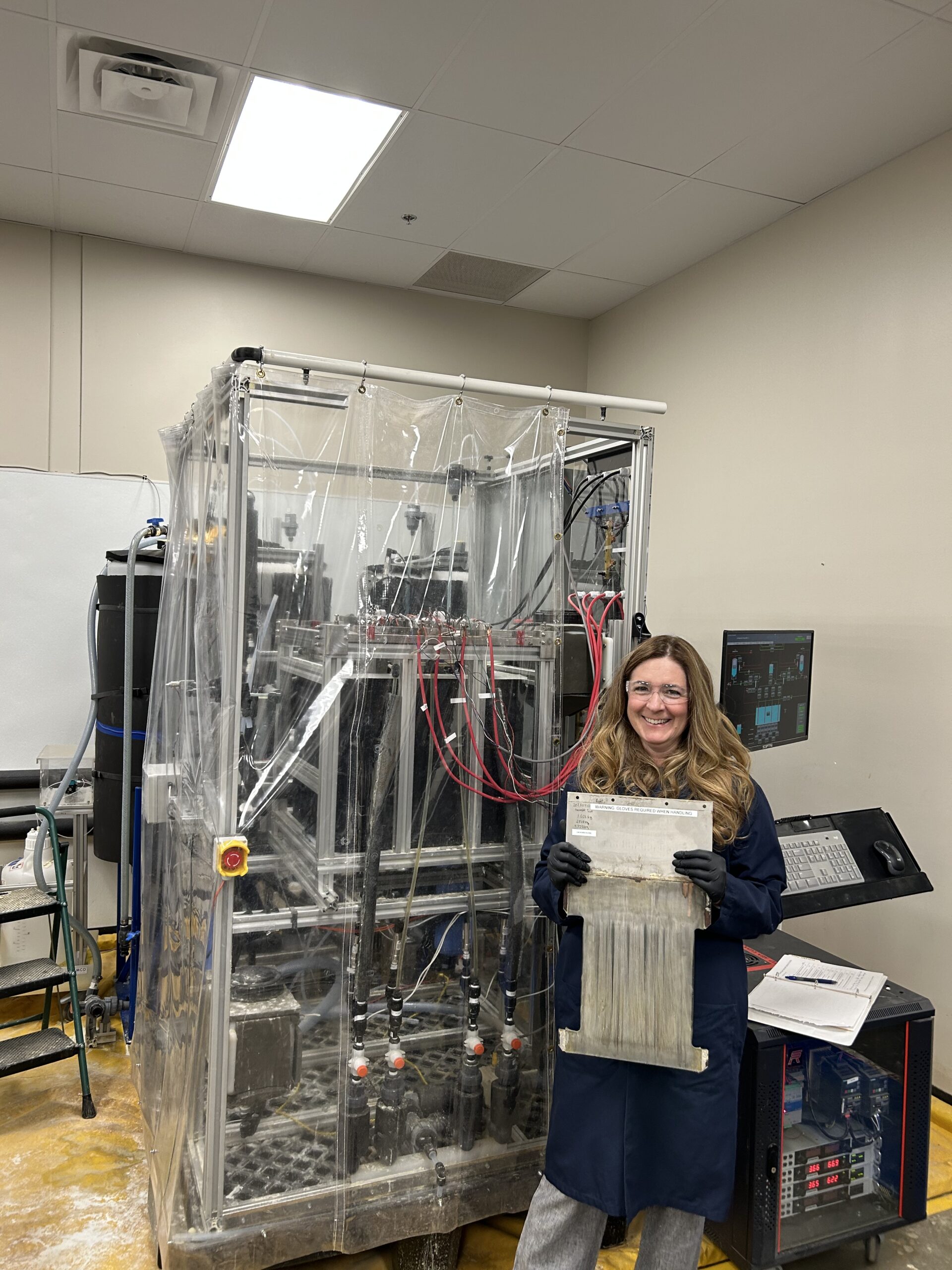

No flames, no coal, no respirator needed: Electra’s senior mechanical design engineer Melissa Mansour holds a plate of pure iron the size of a piece of paper in front of the machine that produced it. Credit: Amena H. Saiyid.

What’s more, Electra, Boston Metal and other industrial startups relying on electricity also face the challenge of finding enough renewable electricity for their operations. Both startups currently draw energy from the grid. And in Colorado and in Massachusetts, where the firms operate, fossil fuels still dominate — though the share of renewables is rising.

Given the varying approaches being used to make steel, the next significant step is to develop government standards to certify that the end product, be it a car or a wind turbine or a building, is made from truly green steel, experts said.

“Every company is defining green steel in a different way and that has to be solved before the industry takes off,” Oxford’s Muslemani said.

Editor’s note: Investors in Electra and Boston Metal include Breakthrough Energy Ventures, a program of Breakthrough Energy, which also supports Cipher.